Of the many pieces of popular culture today, few have enjoyed the broad success of the Twilight franchise. What began as four novels has grown into a multibillion dollar franchise and has gained the fascination of the multitudes. The tale of Edward, Bella, and the paranormal culture they live in shall not soon be forgotten.

When I first

watched Twilight in 2009, I walked

away with an overall dislike of the film, not because it was a romance with

vampires, but rather because I didn’t believe Twilight had the necessary caliber to be

considered quality media. It wasn’t until three years later

that I began watching Doctor Who and

started noticing an increasing number of holes in the vampire movie.

The root causes

for Twilight’s mediocrity are several. Primarily, the characters are shallow,

lacking the necessities of a compelling personality essential for a

developmental arc. While the Edward that expresses undying affection for Bella

gets screen time to no end, viewers get very little exposure to an Edward full

of personal flaws in need of correction. As Matt Inman of The Oatmeal wrote an intelligent article explaining how Twilight,

the book, works, Edward is the manifestation of perfection. This person, who

has excellent looks and superhuman abilities, cares exclusively for Bella, the

fumbling, awkward high school sophomore. But, for all of the time spent

depicting his positive qualities, very little is dedicated to fleshing out

Edward’s character flaws.

Maybe this was

due in part to inferior acting, but viewers are not given much to believe that

the vampires of Twilight are

creatures to be feared. Even though Edward explains to Bella that he is the

world’s most dangerous natural

predator, there is little else he contributes outside of that particular scene

to demonstrate that side. Never, while in a moment of coupled bliss, is Edward

shown struggling to stop his internal predator from devouring his love. Viewers

do not come to the realization that he is a savage time bomb whose bloodlust

for Bella puts her in increasingly greater danger with each passing day they

spend together, for that flawed characteristic is handed to them through unconvincing

exposition. And because the crucial element that could have made Edward a

complex character is so effortlessly handed out, the viewer is robbed of the

emotional experience that might have come with the revelation of what he truly

is.

As a result of

this wasted potential of character flaw, the relationship between Edward and

Bella suffers as a result. Instead of being a platform for character

development, their romance exists for the sake of itself. “Edward intensely listens to everything Pants [codename for an

under-characterized Bella] has to say, even if she's bitching about she had

diarrhea on Christmas or her preferred method for cutting a sandwich in half.” writes Inman in his article.

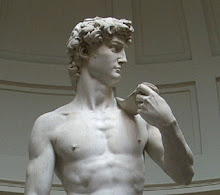

“As far as the reader is

concerned, Edward cares about nothing in the world more than Pants. What the

author has done is created a perfect male figure - a pale Greek statue which

the reader can worship and in turn be worshipped by.”

This relationship

could have been a springboard for a variety of social topics, much like what

George Romero did with the zombie genre. Given that Edward is over a century

old and Bella is sixteen, Twilight

could have easily addressed the topic of pedophilia, either as an in-story

conflict or as a social message. Yet, nobody, either human or vampire, ever

questions their difference in age. Meanwhile, Edward and Bella spend the night

cuddling in her bedroom.

As with the

pedophilia, the film could have made an excellent commentary theorizing what

might happen when an immortal vampire falls in love with a normal human.

Eventually, Bella would have be torn from Edward by the hands of Death while

the vampire lived on in perpetual youth. Additionally, the movie could have

enhanced this theme with the implication that Edward could have had several

lovers throughout his lifetime due to his immortality, each meeting the same

fate Bella would have to inevitably face.

In general, the

Cullen family doesn’t seem to be managing

their immortality very well. Having enhanced speed and strength along with

telepathy and the ability to tell the future, not to mention outstanding

physical looks, tremendously increased the Cullen family’s opportunities to achieve anything they wished, and with

immortality, they had an unlimited amount of time, an incredible resource

itself. Yet, of all the career paths available, they chose to continuously

repeat high school. Unless the family had a particular interest in free

education, this seems to be a waste of time and resources. Considering this

logic hole, Twilight thus seems to

adopt a Panglossian logic; if Edward had not repeated high school dozens of

times, he would not have met Bella, the love of his life.

Ultimately, Twilight is literarily bankrupt. The

plot finds entertainment value in an unrealistic version of high school romance

while neglecting those elements which would have made the story more worthwhile

of the viewers’ time.

Meanwhile, Doctor Who excels where Twilight fell short. The story is

populated by fleshed-out characters who build upon each other for development.

The Doctor, a charming, enigmatic Time Lord, takes viewers on a journey

spanning all periods of time, encountering exotic creatures, notable historical

figures, and ideological extremists; and showing the vast expanse of the

universe. At their cores, Twilight

and Doctor Who share a similar

premise: a normal girl meets extraordinary man who changes her life

forever. However, the approach each

production takes is vastly different. While Twilight

focuses on the relationship of that premise, Doctor Who, much in part to the brilliant writing done by Russell

T. Davies, puts an emphasis on populating its universe with fully developed

characters, which in turn makes for a more fulfilling story.

By far the most

powerful theme present is irony. Like Edward, the Doctor is powerful. Being a Time Lord, the Doctor is universally

acknowledged as a part of one of the greatest races that have existed, and as a

result carries considerable influence wherever he travels. But unlike Edward,

the Time Lord has an outgoing, conspicuous personality and conveys an overall

likability. His compassion toward the human race puts him in danger on a

regular basis, but he shows undying loyalty for his companions as he shows them

the expanse of the universe and beyond.

However, his

jovial attitude and antics are not wholly without motive, for the Doctor

possess his share of negative qualities. Despite all of the variety of life the

universe has to show, the inescapable fact remains that he is the last of his

kind, another major theme in Doctor Who. Below the smile and underneath the charm, The

Doctor is an individual haunted by a war that drove his species into

extinction. No matter where he flies or how far back or forward into time he

goes, he can never escape the ever-present loneliness.

Thus is why he

chooses to bring people along for his journey; he is a character who needs

company. Each of the Doctor’s companions has their

own their own three-dimensional personality with a believable background. Rose

was working as a department store clerk, living with her widowed mother. Martha

was a medical student amidst a dysfunctional family going through a

drama-charged affair. Donna lived a completely superficial life whose height of

existence was the new yogurt flavor or the latest reality show. For these

women, the Doctor provides an escape from the hum drum of reality to an

extraordinary tour of the cosmos, experiencing adventures that the rest of

Planet Earth could never hope to have.

Yet, as amazing

as the journey is, the show constantly reminds viewers that the adventures have

to, and inevitably will, come to an end. The inherent danger of travel in the

TARDIS cannot last, and the companions become burned as a result of standing

too close for too long next to the fire that is the Doctor. Never is the

question if these companions will meet their end, but rather when. Rose gets

trapped in a parallel universe, unable to reunite with the Doctor. Martha grew

fond of him during their travels, but he never showed indication of likewise,

prompting her eventual departure. While saving the universe, Donna gained the

mind of a Time Lord, but such a consciousness could not exist within a human

brain, and the Doctor had to resort to wiping all her memory of him. This is

the irony found in Davie’s Doctor Who. No matter how wonderful, how fantastic a journey with

the Doctor is, the voyage always comes to an unfortunate end, leaving the Time

Lord once again alone.

Qualities like

these are what make Doctor Who

superior to Twilight. The Doctor and his companions are more

compelling than Edward and Bella could be, the more talented writing provides a

more interesting, solid plot, and the acting talents of David Tennant and Matt

Smith (who played the 10th and 11th Doctors, respectively) surpass what Robert

Pattinson did with his character. Should someone decide to rewrite the Twilight Saga long after we all are dead

and the copyright has expired, putting the books into the free domain, he

should take notes from the man in the blue police box, and maybe Twilight will one day be accepted as

quality literature.